There are only two full portraits of the evangelists in the Book of Kells. One of John and one of Matthew at the commencement of their Gospel texts. The remaining Gospels of Mark and Luke begin with intricate illuminations introducing their testaments without the inclusion of author portraits.

At the start of the Gospel of Mark, folio 129v depicts the symbolic representations of the four evangelists, but this should not be confused with an author portrait. Iterations of this imagery also appear in the Gospels of John and Matthew.

Continuing the conversation regarding the symbolic use of color in the Book of Kells, it is interesting to compare the evangelist portraits with the portrait of Christ discussed in the earlier post.

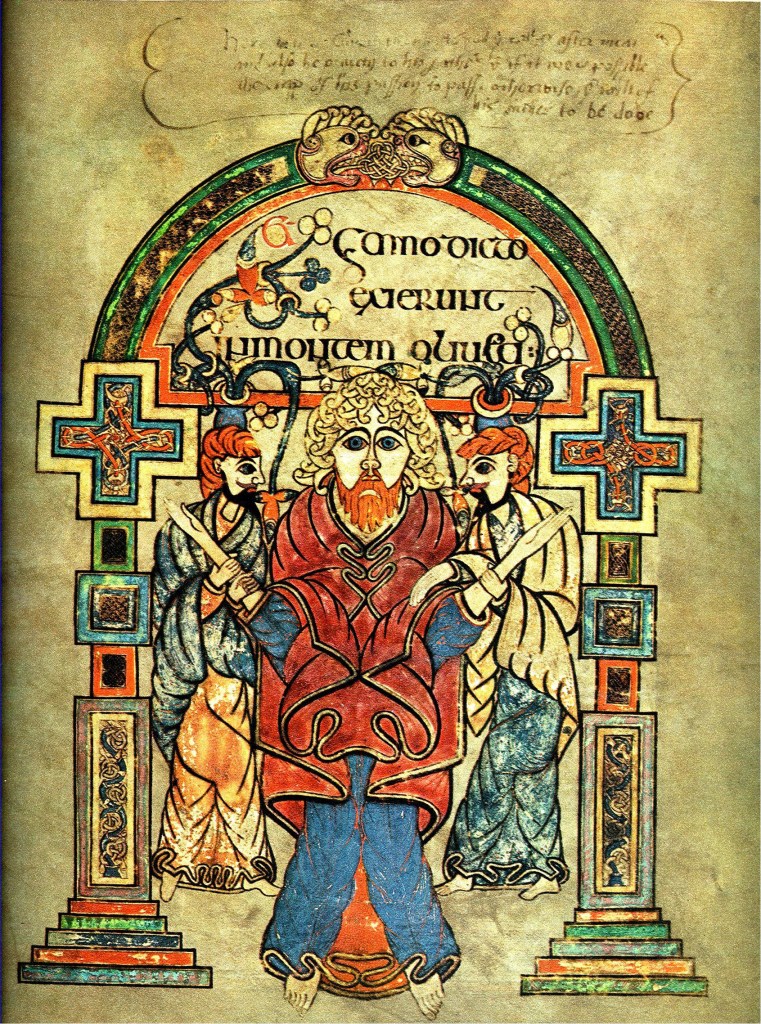

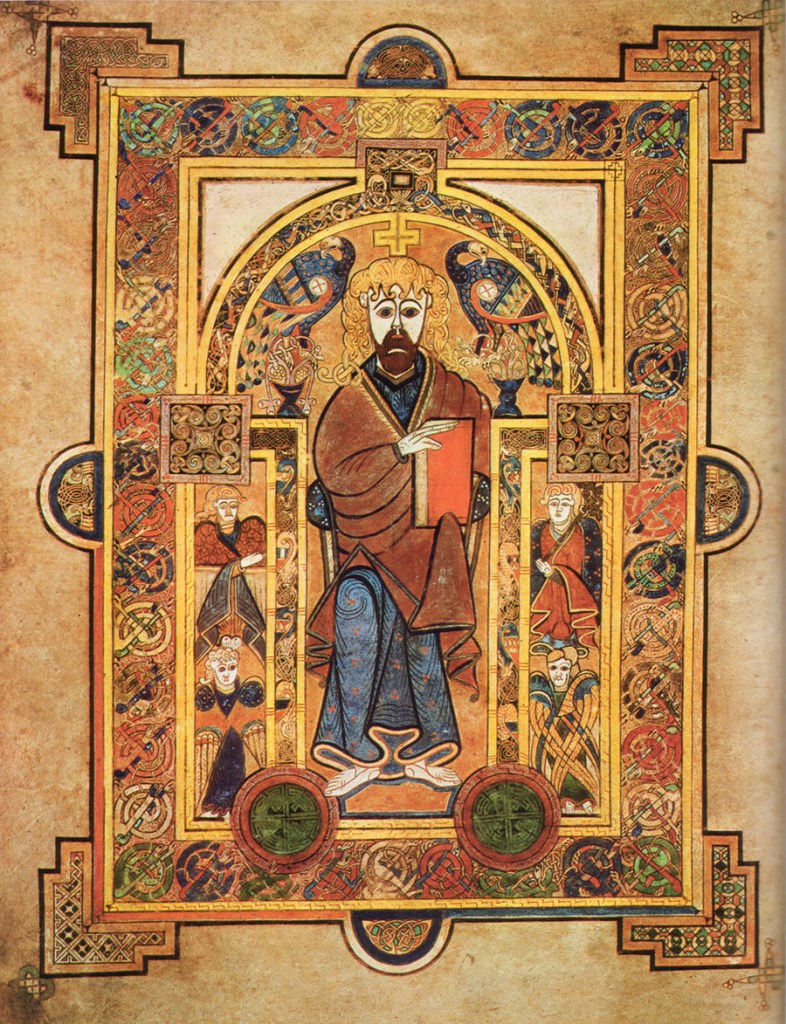

Book of Kells, Folio 291v, portrait of John, Trinity College, Dublin

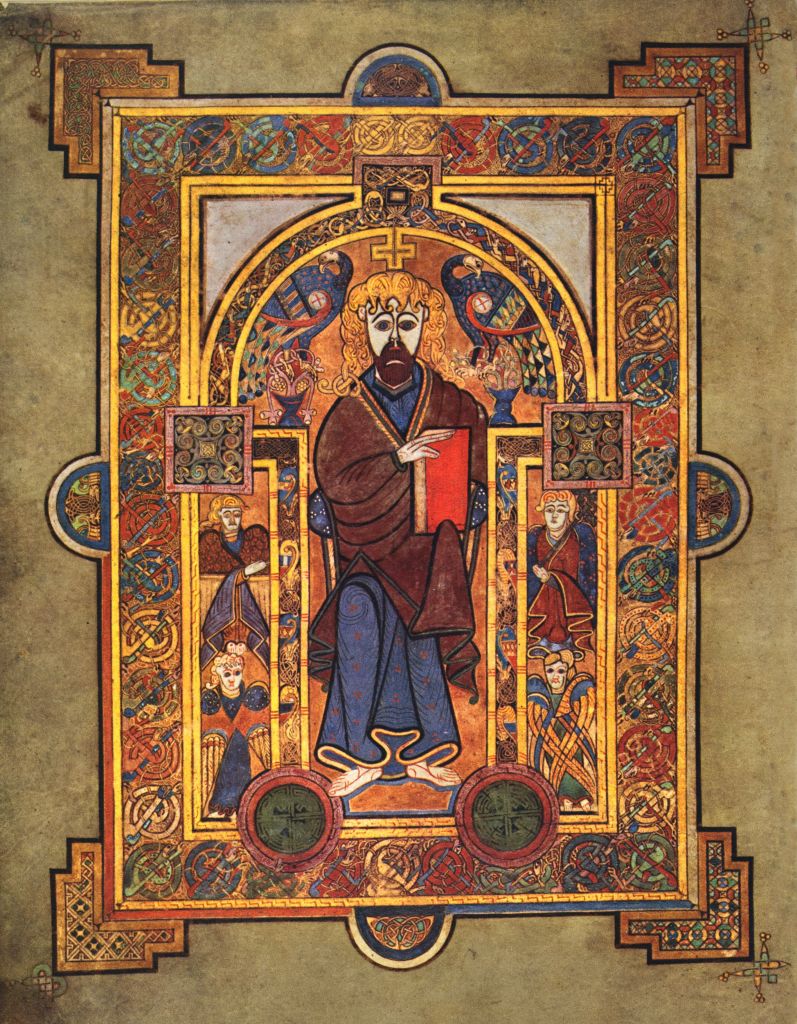

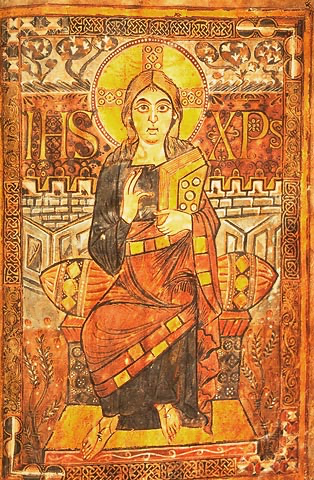

Book of Kells, Folio 28v, portrait of Matthew, Trinity College, Dublin

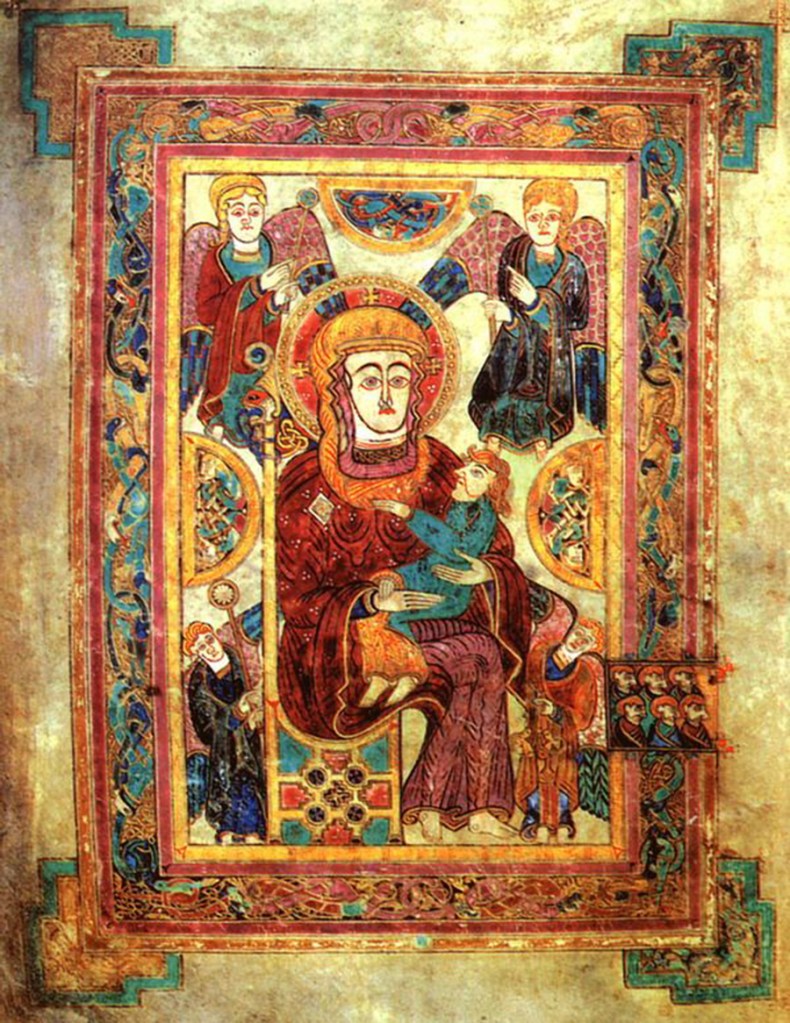

Book of Kells, Folio 32v, portrait of Christ, Trinity College, Dublin

As we can see, both John and Matthew gaze out toward the viewer in a similar pose to Christ’s. However, there are key differences that distinguish them from the realm of the Son of God. To begin with, both of the evangelists have halos, where Christ has a cross extending from his head. The garments of the two evangelists consist of a red robe, similar to Christ’s. However, the tunics beneath their robes are muted earth tones rather than the blue of Christ’s tunic, grounding them in humanity (red), distinguishing them from the divine (blue) nature of Christ.

The treatment of the hair and beards in the portraits of John and Matthew is also interesting to examine. Both of the evangelists have fair hair with slightly darker reddish-brown beards. This color combination is also evident in the portrait of Christ but with heightened dramatic contrast. The gold of Christ’s hair is much brighter, and the reddish-brown of the beard strikingly darker. As compelling as this artistic choice is to investigate in terms of symbolic coloring, we must also consider the possibilities of other reasons for its occurrence, such as fading due to age, as well as the probability that several different hands created these images.