The Medieval Origins of the Graphics on the Irish Pound Note

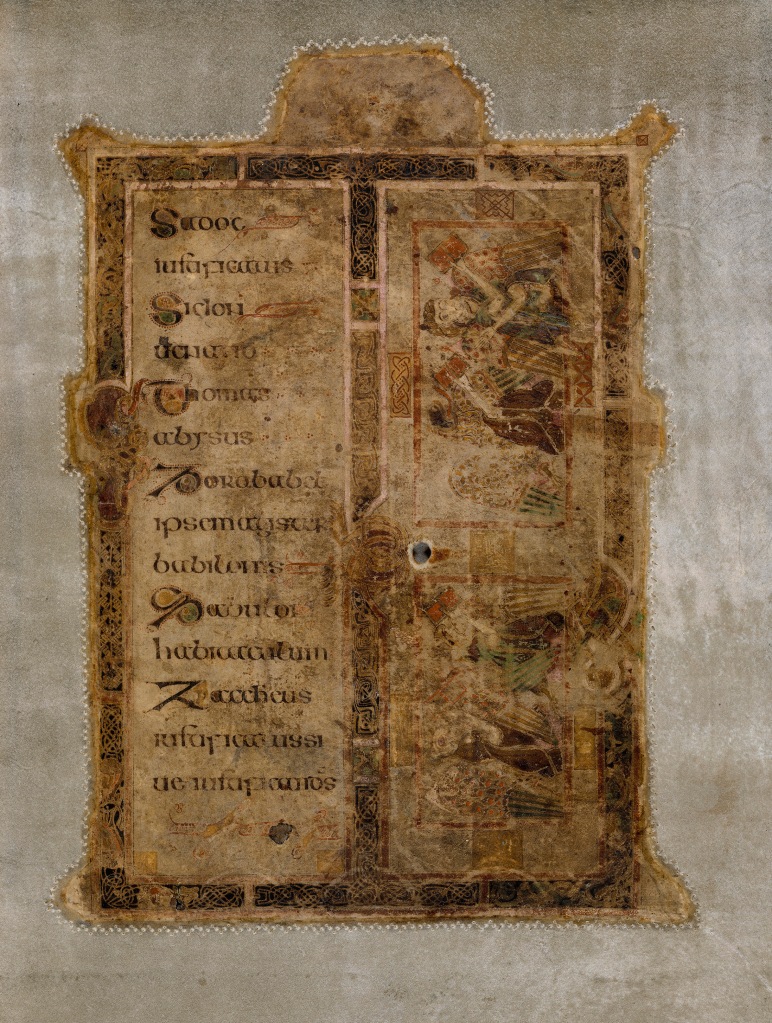

Leabhar na hUidhre, or the Book of the Dun Cow (MS 23 E 25), a 12th-century manuscript, is the oldest extant manuscript in the Irish vernacular. Currently held in the Royal Irish Academy, the book has suffered extensive damage, with only 67 leaves remaining, most of which are incomplete texts. The name derives from a 6th-century sacred relic of Clonmacnoise, the hide of the dun cow that belonged to St Ciarán. St Ciarán’s cow features prominently in folklore and hagiography connected with the saint. According to legend, St Ciarán left home to train under St Finnian at Clonard. On his departure, he asked his mother to let him take one of the family cows along with him to the monastery. When she refused, he set off on his journey, blessing a grayish-brown (dun) cow as he left. The cow and her calf followed St Ciarán to Clonnard, miraculously providing “twelve bishops with their folk and their guests”(1) copious amounts of milk.

Ciarán’s Dun was wont to feed,

three times fifty men in all;

Guests and sick folk in their need,

in soller and in dining-hall.

Anonymous

Upon her death, the Dun cow’s hide became a relic at Clonmacnoise, claiming salvation for the blessed souls.

“The hide of the Dun is in Clonmacnoise, and whatsoever soul parteth from its

body from that hide [hath no portion in hell, and] dwelleth in eternal life.”

The Latin & Irish Lives of Ciaran

The prevailing legend of the book claims that the original vellum comprising the folios in Leabhar na hUidre came from the hide of the scared cow.

The Leabhar na hUidre contains the oldest version of the Táin Bó Cuailgne (The Cattle Raid of Cooley), Compert Con Culainn (The Conception of Cú Chulainn), Bricriu’s Feast and other religious, mythical, and historical material. However, it is probably most recognized as the print on the reverse side of the Irish One Pound note, circulating throughout the Irish banking system until 1989. The Queen Medb £1 Note featuring the warrior Queen on its front came into service in June 1977.

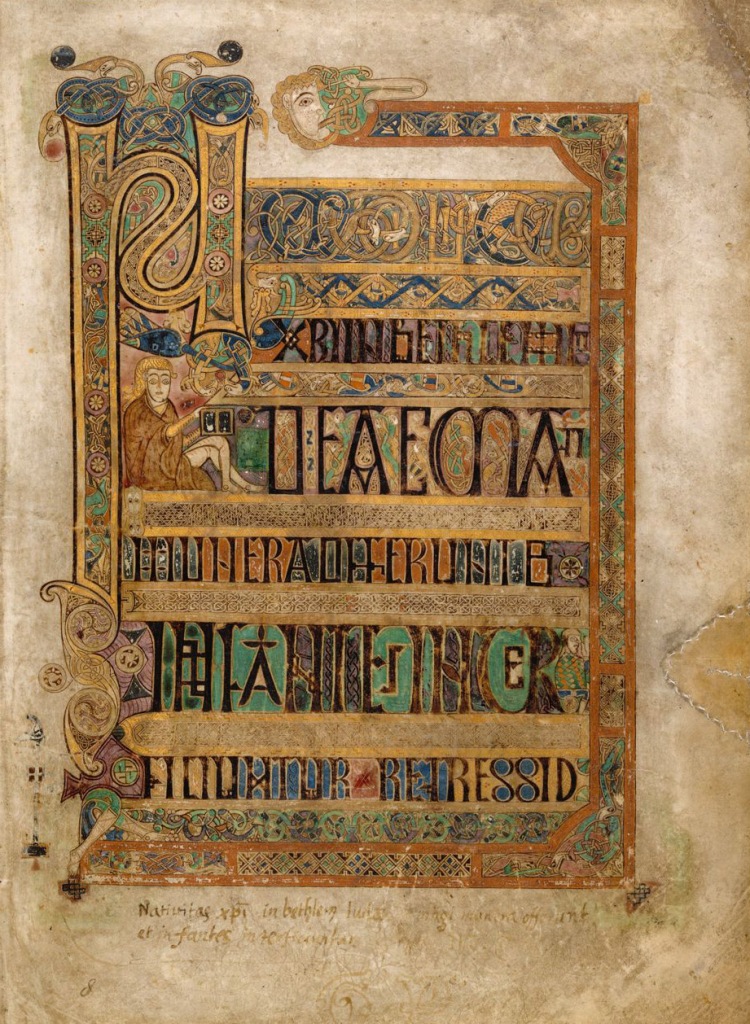

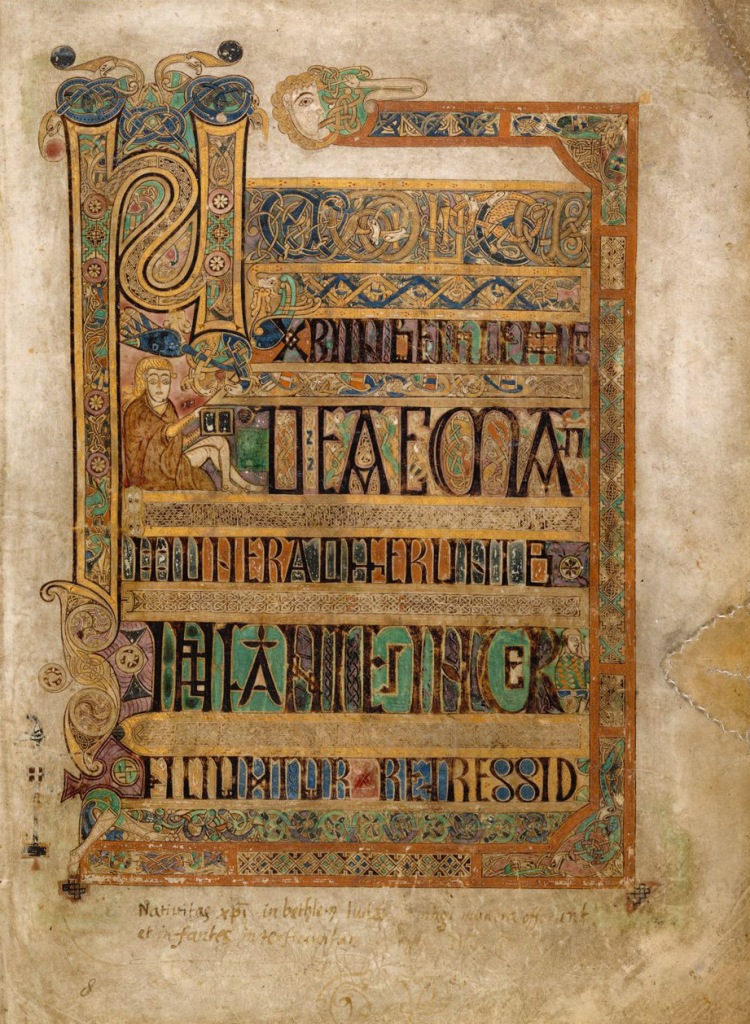

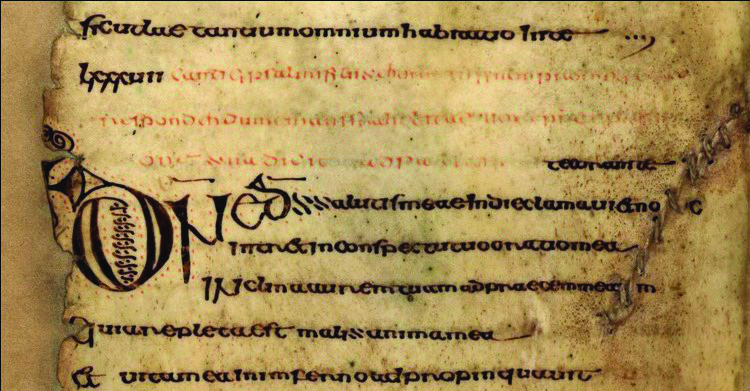

On the reverse side was a graphic portraying an extract from page 77 of MS 23 E 25 (The Book of the Dun Cow). The excerpt is from the Táin bó Cuailnge (The Cattle Raid of Cooley). Sometimes referred to as the “Irish Iliad,” the Táin tells the story of Queen Meave of Connaught’s war, waged against Ulster to capture the stud bull Donn Cuailnge (the brown bull of Cooley), a mythical creature who was once a human.

The passage on the pound note highlights a decorative initial “R” in red and green ink, probably adapting the original colors to comply with the two-tone currency printing regulations. In comparison, the manuscript uses yellow, purple, and red as the primary colors and exhibits evidence of wear and tear, which the graphic reproduction eliminates.

Courtesy of Banc Ceannais na hÉireann

Royal Irish Academy, Dublin

The designers of the Irish currency in the late 1970s chose a book with associations to a sacred brown cow and further chose a passage from a tale involving a mythical brown bull. If these decisions are deliberate, one wonders if the “cash” cow pun was intentional or if it was merely a coincidence when combining Queen Maeve’s image with a narrative from her history.

(1) Anonymous, “How Ciaran Went With His Cow to the School of Findian,” The Latin & Irish Lives of Ciaran, (06/12/2017), https://www.moboreader.com/readBook/16253322/328757/The-Latin-Irish-Lives-of-Ciaran.

(2) For the digitised manuscript visit: https://www.isos.dias.ie.