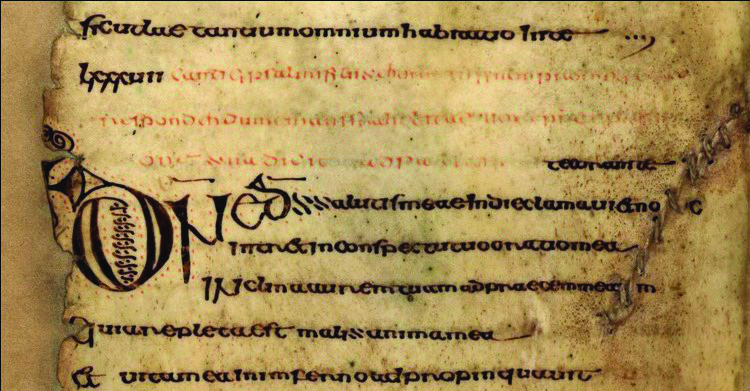

St. Columba (521-597) founded a group of several significant monasteries in Ireland and Scotland. The Cathach, a sixth-century copy of the psalms in Latin, is traditionally ascribed to him and is the oldest extant Irish manuscript of the Psalter. The book’s decoration contains many elements of early Christian art but does not contain the interlacing scrollwork that would later become one of the hallmarks of Irish illumination. Many of its elaborated initials are directly related to the La Tène style, while others incorporate crescent-shaped motifs with conjoined spirals reminiscent of the Celtic Neolithic era symbol of the triskelion. An additional ornamental initial depicts a fish bearing a cross, a widely used Coptic motif suggesting a Mediterranean influence.

Ornamental initials from the Cathach,

6th century,

Royal Irish Academy

Ornamental initial from the Cathach,

6th century,

Royal Irish Academy

Another embellishment used in the calligraphic decoration is diminuendo. This textual design comprises a large capital letter followed by smaller letters, decreasing in size until equivalent to the lower-case size of the body of the text. This technique would be used to an even greater degree a century later in the Book of Durrow.

Folio 48r from the Cathach, 6th century,

Royal Irish Academy

Folio 44v from the Cathach, 6th century,

Royal Irish Academy

Sources:

- “The Cathach / The Psalter of St Columba.” Royal Irish Academy. April 15, 2021. Accessed May 24, 2021. https://www.ria.ie/cathach-psalter-st-columba.

- Mitchell, Frank. Treasures of Early Irish Art. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1977.