The connection between the iconographic styles of Coptic and Celtic art extends beyond the scrollwork so readily identifiable, particularly in the Insular manuscripts. Composition and figural representations also bear considerable similarities.

Early Coptic Christian icons are discernible by indicative features such as sharp outlines, flat colors, simplified shapes delineating folds in fabric and facial features, without concern for realism. One of the most prominent features of the style was the eyes of the figures portrayed. The eyes are large and do not seem to gaze upon the viewers but beyond and past them. This deliberate artistic choice is symbolic and carries a meaningful divine message, as do many other aspects of the facial features in Coptic iconography. For example, the eyes were rendered large and with simplistic shapes to symbolize the ability to look beyond the material world to transcend into the light of God. Similarly, the artists diminished the nose and mouth to deemphasize sensuality and ill words while enlarging the ears to emphasize the importance of listening to the word of God. (1)

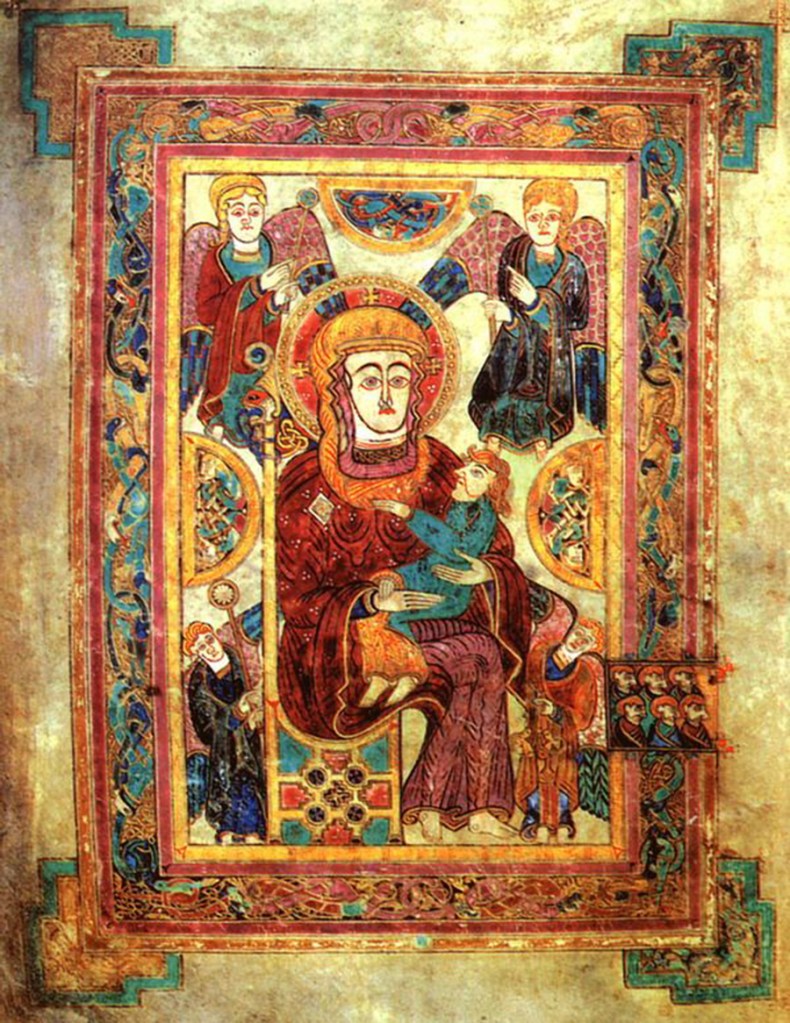

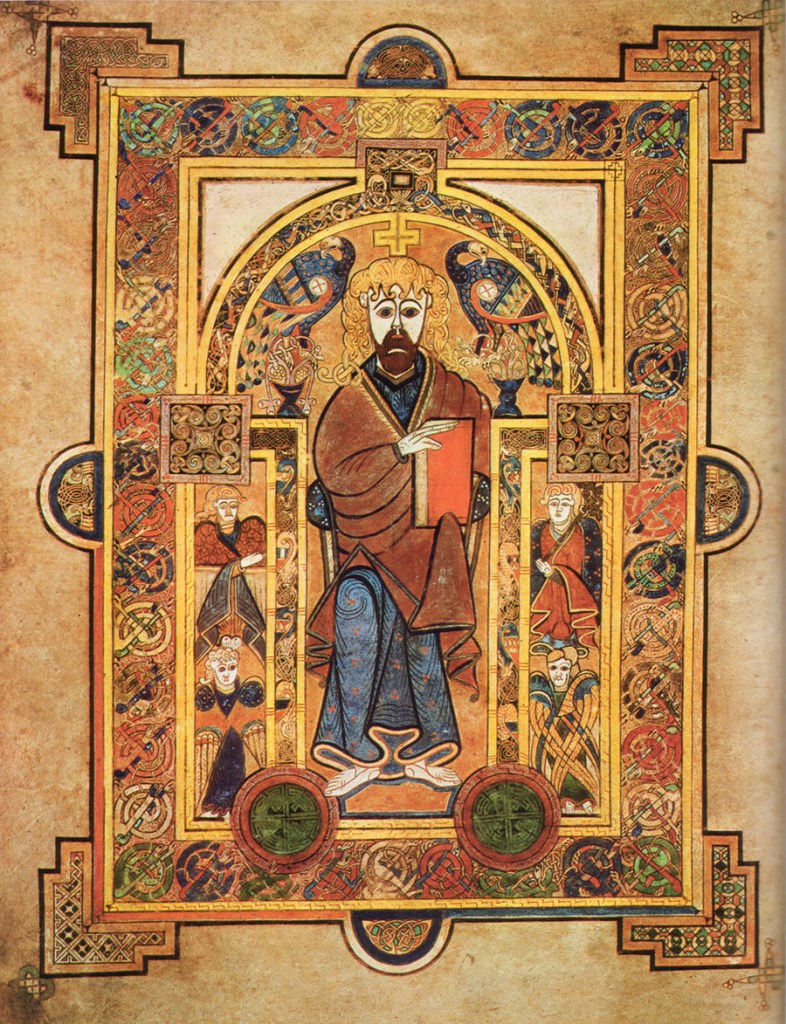

Many of these characteristics appear in images outside of the Coptic Church. Indeed they can be found in the Book of Kells (early 9th-century) illuminations. Although the imagery in the Book of Kells has become somewhat more ornate, the facial attributes in the figures seem to emulate the Coptic traditions of form. For example, the face of Christ in folio 32v from the Book of Kells bears a striking resemblance to the visage of Christ in the 7th-century wall painting from St. Antony’s Monastery in the eastern Sahara Desert of Egypt.

These examples also seem to be following in Coptic traditions of composition. Below, the central figure of Christ from the Egyptian wall painting is enthroned and surrounded by four angels. Likewise is the illumination of the Madonna from the Book of Kells (folio 7v). In this comparison, the Coptic Christ is presented as “Pantokrator”—holding the new testament in his left hand while making a gesture of blessing or teaching with his right. The angels flanking him represent the Seraphim and Cherubim, who praise Him as the incarnation of God. Thus, these angels also flank the Madonna and Child to emphasize that the divine child in the Virgin’s lap is Christ the Lord. (2)

The Virgin and Child. FOL. 7 V. Book of Kells, .c 8th – 9th century, Trinity College, Dublin

Wall Painting of Christ Entroned.

7th century, Monastery of St. Anthony, Egypt.

Christ Enthroned. FOL. 32 V. Book of Kells, .c 8th – 9th century Trinity College, Dublin

The image of Christ enthroned from the Book of Kells is also a curious interpretation of Christ as Pantokrator. Here Christ holds the Bible in His left hand, but although He presents His right hand in a gesture of blessing, it is placed upon the book rather than held up toward the viewer. Perhaps this is to signify the sanctification of the word of God or to bless the sacred Book of Kells itself.

The similarities between the Christian imagery from these geographically disparate lands are compelling. So how did these iconographic ideas reach the distant shores of Ireland?

(1) Capuani, Massimo, and Otto Friedrich August. Meinardus. Christian Egypt: Coptic Art and Monuments through Two Millennia. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2002.

(2) Sawires, Dr. Paula. “Coptic Iconography and Orthodox Theology.” Egyptian Christian Art (blog). Accessed March 3, 2021.