In early Christian art, the symbolic meaning of color was significant for expressing the characteristics of the portrayed figures. As an essential element in iconography, each color represented specific traits or properties attributed to the depicted icons and elements. These notions of symbolic colors were widely used but not inflexible. Often artists rendered their interpretations of the canons of iconography, resulting in representations that varied according to region, culture, and period.

In the Book of Kells, for example, eight-core pigments have been identified. Below is a chart listing the pigments with their corresponding iconographic values.

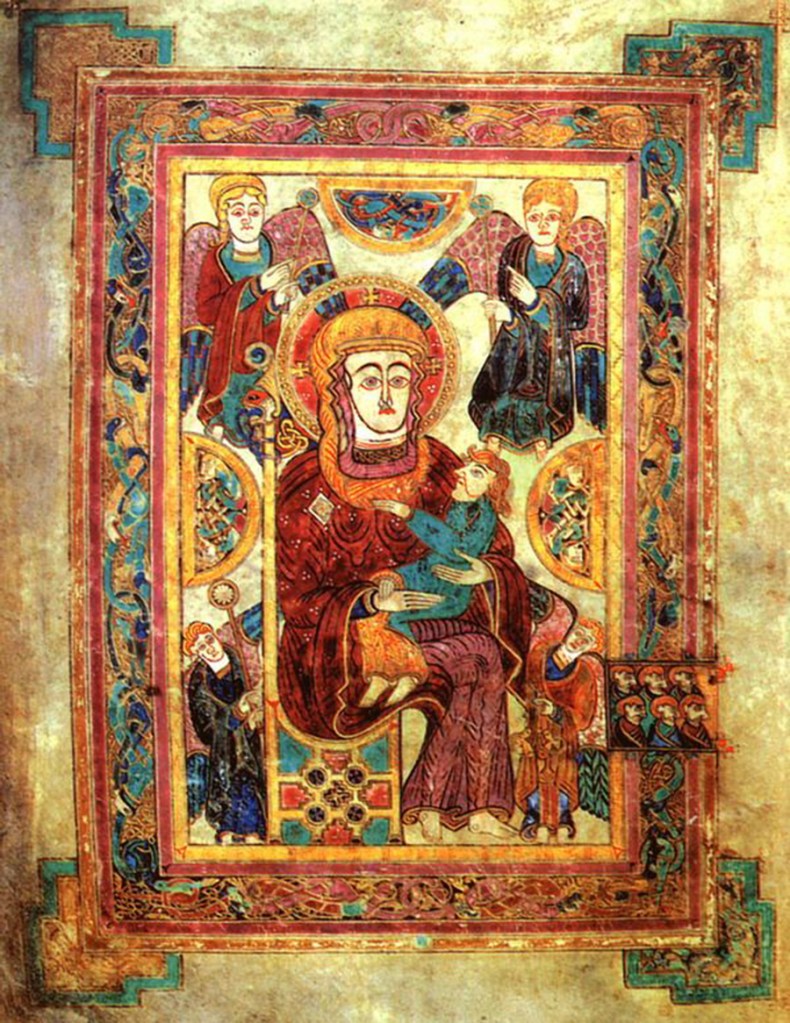

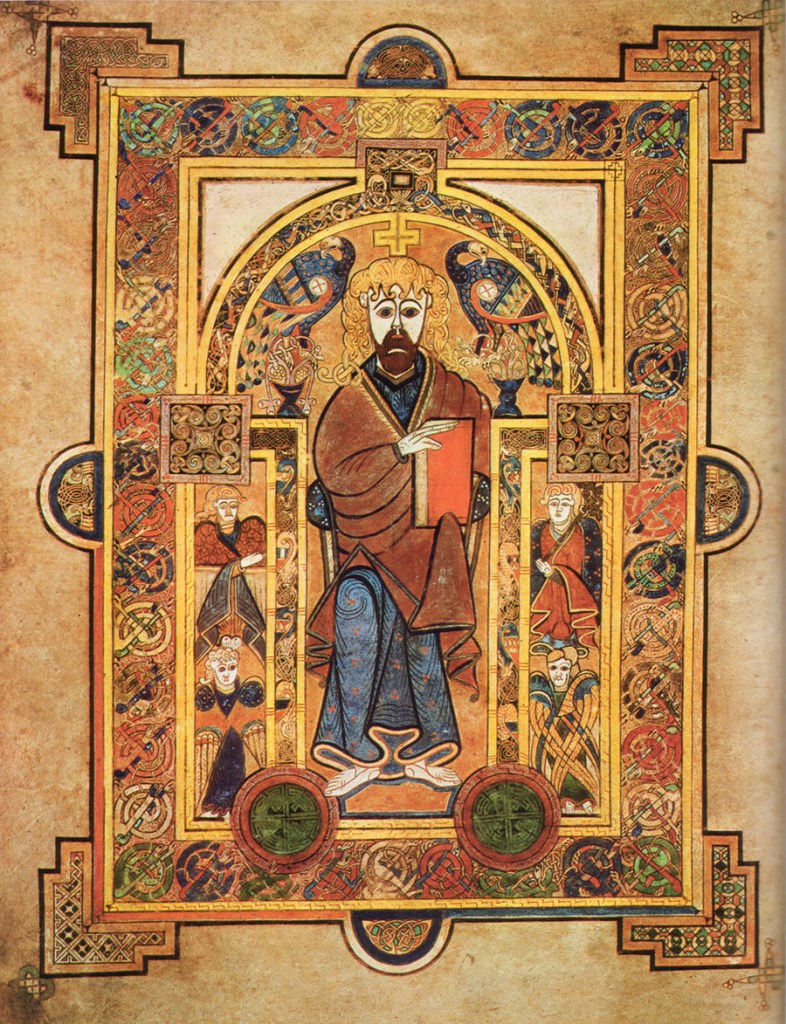

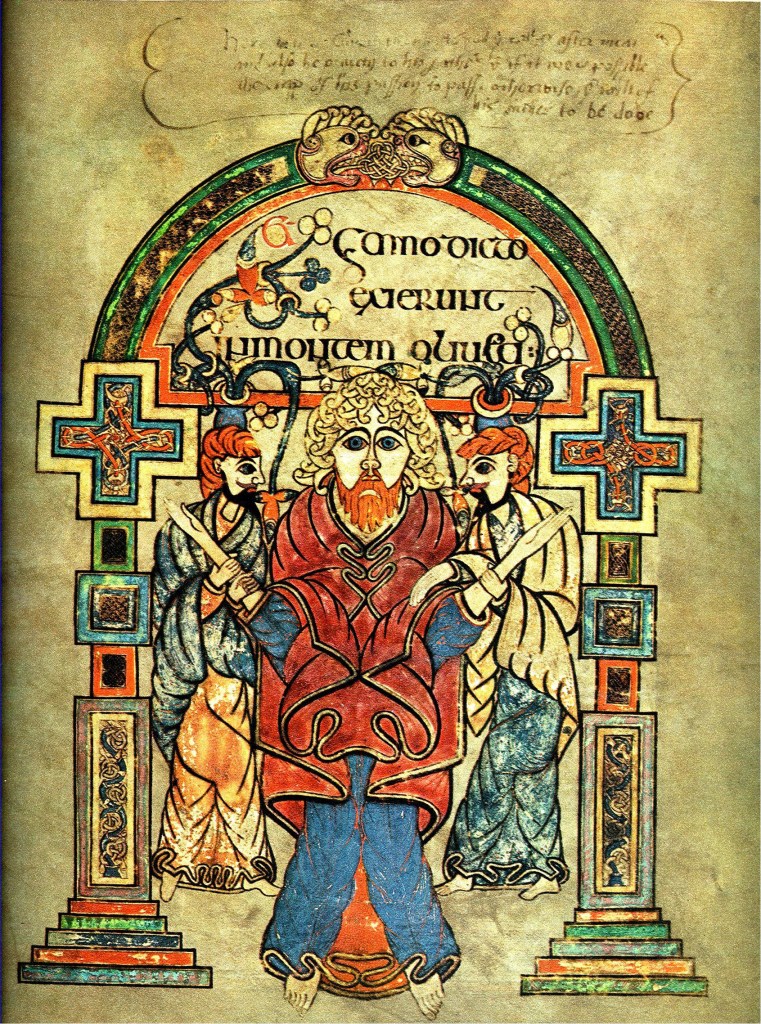

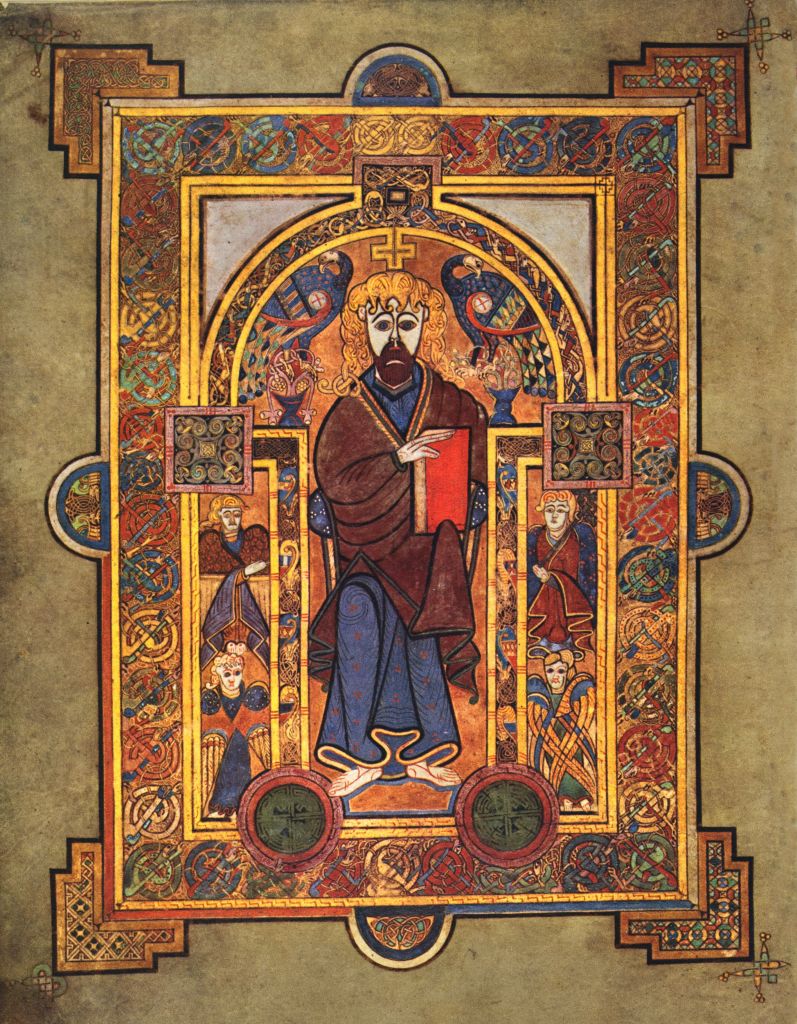

It is interesting to question the intent of the artisans of the Book of Kells while taking note of the varied use of the tenets of color symbolism in these two images of Christ. Here, the artists chose to depict Christ with fair hair and a reddish-brown beard.

The Book of Kells, fol. 114r: the arrest of Christ,

Trinity College Dublin

The Book of Kells, fol. 32v: portrait of Christ,

Trinity College, Dublin

One way to begin a potential analysis of this artistic choice is to examine the texts these images illustrate. Both of these images appear in the Gospel of Matthew, whose opening line in the Vulgate reads:

Liber generationis Jesu Christi filii David, filii Abraham. (The book of the generation of Jesus Christ, the son of David, son of Abraham.)

Matthew 1:1

1 Samuel 17:42 describes David as having reddish hair, so perhaps the auburn beard of Christ references Matthew’s assertions of Christ’s adoptive lineage to David through Joseph. Nevertheless, this does not explain the fair hair on his head. There are no physical descriptions of Jesus in the Gospels; however, in Matthew 17:23, the transfiguration of Christ provides the following description:

et transfiguratus est ante eos. Et resplenduit facies ejus sicut sol (and he was transfigured before them. And his face shone as the sun)

Matthew 17:23

Perhaps then, the golden yellow hair of Christ in the Book of Kells is symbolic of the Glory of God, therefore, representing the duality of Christ’s human and divine incarnations. As we can see, His costume consists of a blue tunic with a red robe which further signifies His divinity and humanity.

However, for this analysis to be considered a viable resolution, Christ would need to be the only figure in the book depicted with these traits, consistently discerning Him from any other persons. Further investigation of the illuminations is necessary for constructing this argument.

Sources:

“The Book of Kells.” The Book of Kells – The Library of Trinity College Dublin – Trinity College Dublin. Accessed April 22, 2021. https://www.tcd.ie/library/manuscripts/book-of-kells.php. https://doi.org/10.48495/hm50tr726

“Internet Sacred Text Archive Home.” Internet Sacred Text Archive Home. Accessed April 22, 2021. https://sacred-texts.com/bib/vul/index.htm.